'Art Bastard' profiles Bob Cenedella and the contemporary art world

By Diane Carson

Director Victor Kanefsky's documentary Art Bastard profiles contemporary, anti-establishment artist Robert "Bob" Cenedella, born in 1940. In so doing, the film offers a provocative profile of the art world, primarily because, as Bob says, "There are no words to describe my feelings. I despised it." The film's title Art Bastard is both literal and metaphoric.

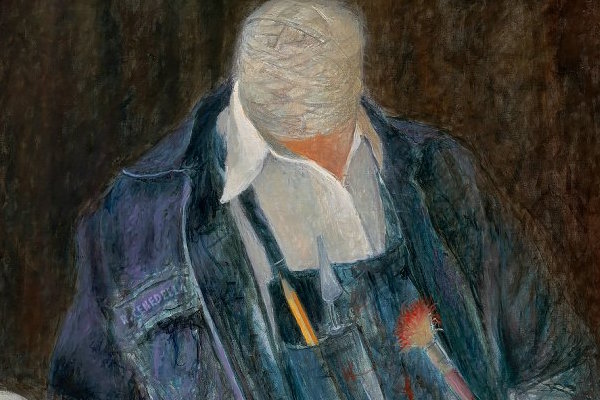

Bob Cenedella learned at six years of age that Robert, Sr., his alcoholic mother's husband, was not his actual father. He was Russell Speirs, Colgate University professor, but Bob says the two of them didn't amount to one real father. Though expelled from high school (a great story), at the Art Students League of New York, Bob found his perfect teacher: George Grosz. A refugee from Nazi Germany, Grosz encouraged Bob to "think with your hand," and Bob translated New York's energy and teeming masses into paintings crowded with discord.

And yet in Bob's professional life, the art community rejected or marginalized him, not because Bob lacked talent but due to his satirical approach to icons of American culture. For example, in a response to civil rights protests, he put dogs' heads on policemen and policemen's heads on dogs. He made Nixon and LBJ dartboards. For his 1965 "Yes Art" show Bob gave out Green Stamps, mocked Warhol and pop art, and then didn't paint for ten years. But he decided "not to be a tragic figure," and in 1985 painted a Hitler orchestra conductor with audience members also sporting Hitler moustaches. And then Saatchi and Saatchi took Bob's painting of Santa Claus on a cross out of their 1988 one-man show for Cenedella. Regarding the art world's taste for mediocrity, Bob comments, "It's not what they do show but what they don't show that bothers me."

Unrepentant today, Bob asserts that when he painted the New York stock exchange in 1986, he found it nice to deal with "honest crooks rather than the kind I deal with in the art world." Director Kanefsky inserts interview footage of Bob's sister and son (among others), archival photographs and video footage sufficient to add context to Bob's vivid, colorful work. It is amply represented with Bob's own informative commentary. The music, however, is uneven, sometimes nicely interpretive and, at other times, loud and intrusive. Described as a pugnacious character, Bob is refreshing, cutting through cultural hypocrisy. Bob Cenedella brings all the drama necessary to make Art Bastard a compelling portrait. The end credits list the paintings shown in the film, identifying the artists and the museums. What a great idea! At Landmark's Tivoli Theatre.