‘Faust’ imagines an inventive interpretation of the fable

By Diane Carson

The Dr. Faustus legend eloquently warns against selling one’s soul to the devil for twenty-four years of knowledge, power, and pleasures. Known popularly as a Faustian bargain, when allotted time expires, Mephisto comes to collect his payment. Numerous authors, folktales, and films have interpreted and adapted the essence of this cautionary tale, but none with Czech surrealist Jan Švankmajer’s imagination.

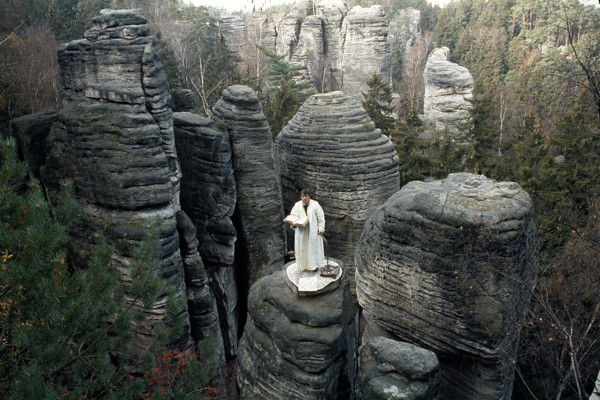

Combining live action, claymation, life-size marionettes, and puppetry with stop motion moving theater flats and furniture, Švankmajer gives a perplexed modern-day Prague businessman the central role. Faust emerges from the subway, is handed a map by two men who erratically reappear, eventually seeks out a theater, and acquires the Faust costume, emerging occasionally onto a stage with a live audience. At other times, he wanders, debates, and pursues his desires, interacting with animated characters, some grotesque, all unpredictable.

Ricocheting from humorous interludes to frightening exchanges, Faust teases out philosophical ideas while he never is able to exercise the complete control he desires. Flights of creative invention include alchemy, a black chicken and a black dog, an egg discovered in a loaf of bread (though the egg is as empty as Faust’s soul), Faust’s clay head morphing into various shapes, a trip to Portugal for a David and Goliath match before a deluge, a severed leg that reappears, and other absurdist elements, which is exactly the point. In addition, Švankmajer often cuts to hands manipulating the puppet strings, keeping the artifice intentionally visible. Sound, music, and sound effects add another layer to the Kafkaest feel, enhanced by Petr Čepek’s performance as Faust.

To grasp this “Faust,” Jan Švankmajer notes it is essential to study the activities of the Surrealist Group in Bohemia, of which he has been a member since 1970. Jan writes that “a common denominator for all my films . . . has to do with getting rid of anxieties and fear.” He certainly indulges and liberates his unfettered imagination, drawing liberally on Goethe, Marlowe, Christian Dietrich Grabbe, and others, all acknowledged in the credits. I’m not sure if I’ve rid myself of or intensified my distress, but “Faust” is a wild, wonderful ride. In Czech with English subtitles, “Faust” is available through the KimStim website with a link to the Webster University Film Series.